By: Jessica C. Neal, Project Scholar

“Who made you,” was always the question. The answer was always “God.” – Alice Walker

Places of worship hold a special significance for many individuals, offering spiritual solace and a sense of community. In the deeply interwoven fabric of our society, diversity of faith is the thread that weaves together the multifaceted experiences and stories that define our communities. Faith communities provide emotional support, a sense of belonging, and community. Not only does faith shape identity and purpose, it helps to emphasize one’s worth which helps to combat negative stereotypes and fosters self-acceptance.

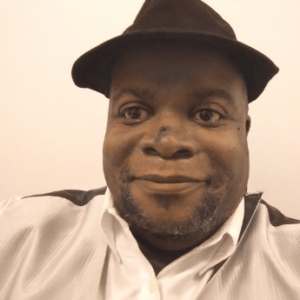

This addition to the Intersection of Race and Disability Project will focus on a true bright light and deeply missed community member, David Hale (1979-2020). David was a Black Pittsburgh native living with the congenital condition, spina bifida. Before succumbing to cancer at age 40, David was a musician, poet, motivational speaker, youth minister, and beloved brother and friend. This article will explore the remarkable journey of David’s determination, friendship, artistry, and faith that kept him motivated throughout his life.

As Tonya Hale, David’s sister, remembers it, the doctors told their mother that David’s life expectancy would only be five years. Receptive of the doctor’s news, but being deeply planted in her faith, their mother would constantly remind David throughout his life that only God determines our time on Earth, and with that motivation, David set out to celebrate and live life to his fullest potential.

Charlotte Jackson gave birth to David Hale on November 28, 1979. David was diagnosed with spina bifida at birth. Spina bifida involves the incomplete development of the spine, and is a permanent condition that impacts people throughout their lifetimes. As a young person, David wore a body cast as a form of orthopedic management. Eventually, David was able to transition from the body cast to a wheelchair, which he used independently throughout his childhood and adulthood.

David grew up in a loving and supportive environment with his mother and three siblings who made his home life as typical as possible. Tonya recalls: “We had a really good life. I mean, we were poor, but we had a really good life, you know. My mother was in [the] church, and she was taking care of four kids by herself. One [son] with a disability, and [my mother] also had epilepsy. With prayer and God she kept us together, and life was good.”

As a student, David attended Pittsburgh’s Pioneer Education Center. At Pioneer, David engaged in an intensive program driven by an Individualized Education Plan (IEP). IEPs are created to help children develop diverse skills in a school setting, in areas such as cognitive, augmentative communication, speech and language, occupational therapy, physical therapy, hearing, and vision. It was at Pioneer where David’s creativity began to fully take form, starting with an interest in prose and poetry. Tonya shared:

“It [writing poetry] started when he was going to Pioneer. I guess seeing the disparities not just in himself, but in other people with spina bifida that was worse off than he was, kind of inspired him, especially with the writing. I was really shocked at the writing. I said, ‘What made you start? Why are you writing?’ You know, and he said that it was just something that he wanted to do, and he started doing it.”

David graduated from Pioneer in 2001. After graduation, David had his sights set on building a home and life for himself independently, and like most things he had set to accomplish in life, he would succeed. He found an apartment in McKees Rocks, a suburb of Pittsburgh about 4 miles northwest of the city. McKees Rocks, also known as “The Rocks,” is a borough in Allegheny County along the south bank of the Ohio River.

Though in his early adulthood, he was determined as most to experience his full independence and explore life as an adult. It was there, in 2003, that he met someone who would become a lifelong friend and companion, Varnum Holland. Holland was a neighbor at the apartment complex, and, due to his self-described extroverted nature, he was the one to make the first move. When asked to share how they met, Holland told a story that is symbolic in many ways of the relationship and bond they shared. From Varnum, affectionately called Varney:

“I was driving into the parking lot and he just rode by [in his wheelchair]. He liked to do laps around the condo for exercise. I had just come home from church. He was a quiet man, and I’m an extrovert. So, I was like, ‘Hey, how you doing? What’s going on? I’m Varnum Holland, pleased to meet you.’ I was just being kind and stuff, and said, ‘Hey, would you like to come to church with me someday?’ And he said, ‘Sure, I like church,’ and we found that we had the same faith. We were both Christians and that was my earliest memory of meeting David.”

Over the next several years, the two became quite the traveling buddies. Tonya remembers: “I think they’ve been to every state, every country, everywhere. Then with Varnum being an inspiration to him, them being an inspiration to each other. They became very, very, very good friends. So I really wasn’t really worried about him because I knew that, you know, he had Varnum with him, and they were really good.”

The friends shared more than just a love of travel, exploration, and adventure; their faith and creativity were a huge part of what bonded them, and was the passion that drove David throughout his life.

Through Varney, David became a member at Saint Stephen’s Anglican Church [formerly, St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church] and later took on the role of Youth Minister. David’s power to inspire with words extended beyond his poetry and ministry, he became a renowned public speaker at schools and other venues. Being able to share the disparities he saw in the world through his creative outlets was important to him. His sister speculated that as a person with spina bifida, he was able to see and recognize not just the disparities impacting himself, but also those in the broader community around him. This allowed him to connect and give a narrative in a way that touched many.

David was able to achieve his aspiration of living his fullest life, as well as living independently, until the last few years of his life. After he was diagnosed with cancer, he and his family eventually made the decision to transition David into a hospital environment where it would be easier for his family to get to him and for him to receive adequate care. After a long fight, David Hale succumbed to his illness and passed away at age 40, far past the initial life expectancy of five years predicted for him. His mother was right.

Of his legacy, Tonya remembers: “I try to be positive. I try not to complain, because, you know, he has accomplished so much and I try to live my life every day, you know, as positively as I can. You know, because he has been through so much, and I’ve never heard him complain. You know, I never heard him whine or say, oh, I don’t know if I can do this, or I don’t know if I can do that, or this hurts, that hurts. In the 40 years of his life, I have never heard that man complain. Not ever. So that’s my inspiration, you know, is to try to be the best I can be, and try not to complain.”

The experience of being both Black and disabled is as unique as it is emblematic of the daily challenges faced to survive in America by people of color. Historically, both the Black and disabled communities have faced marginalization and discrimination, with Black disabled individuals providing a vital voice for the doubly marginalized. The work of Black disabled activists and allies shed light on the challenging experiences in accessing healthcare, education, advocacy, and employment. Further, Black disabled individuals underscore how disablement is often complicated by the precarious intersection of ableism and racism.

Despite these challenges, the Black and disabled are still able to lean into joy, advocacy, determination, and community building. When asked how David’s legacy lives on, Varney replied “His catchphrase was ‘celebrate life.’ That’s what I do all the time. That’s what I do. Celebrate life. That’s not to say bemoan death, because he and I both believe we’re going to heaven when we die, and that’s a better place, but celebrate life. Live life to its fullest. Be in the moment. Don’t get lost in the shuffle. Just be. Exist within each other’s presence.”

For Further Reading

- Szweda Jordan, Jennifer. December 17, 2020. The loss and legacy of a motivational storyteller and ‘encourager’.

- ADA at 30: Accessibility in Pittsburgh. July 17, 2020. Podcast episode 4: Three people with disabilities talk about how disability affected their faith.